A mathematician is a device for turning coffee into theorems – Alfréd Rényi

One of the notable limitations of a standard autoregressive model is that it intrinsically assumes distributive homogeneity across the historical time horizon. A system’s impulse response to a change in the value of a shock term, , at some time-step,

, must also account for influences imposed by external systems evolving in parallel – specially if there exist a correlation known to be of particular significance. These nuanced characteristics of real-world scenarios further complicate an autoregressive model’s broad application as a time-varying forecast. This new series explores mathematical machinery borrowed from Itô calculus as a means to derive a systematic solution to an n-state autoregressive model where significant correlation exists between two interacting time-varying processes with underlying random components.

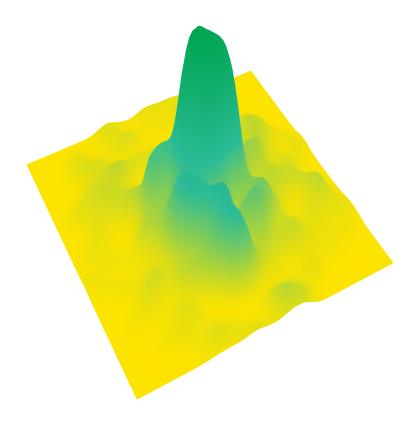

Imagine a singular stationary point in a closed system. An infinitesimally small region containing within it maximum information in a state of equiprobability. In a state of such rigid order the propensity for information mobility is minimized. Now consider allowing this system to interact with another time-varying process. The structural stability of our information space due to volatility from information gain, deteriorates as its entropy increases. This process is accelerated as our system evolves forward in time.

Suppose that the entropic state for the subset of initial information , observed at time

, is bound by the preceding entropic state at time

. Therefore, in the case of discrete intervals we have

where is a scale parameter and

represents white noise. Rearranging the terms in (1) we can show

This result derives from the fact that the first difference of a random walk forms a purely random process. The analogous interpretation of (2) in continuous time can be described by the general form

This expression is what is commonly called a first-order continuous autoregressive equation CAR(1). A CAR process of order is generally represented by the following equation

Note that represents a continuous white noise process which cannot physically exist. We will instead replace this term with one that represents small infinitesimal changes characterized by Gaussian orthogonal increments. That is to say that for any two non-overlapping time intervals

and

the increments

are independent of past values

. Furthermore,

is always zero.

is described as pure a Wiener process. We will rewrite (3) in its first-order stochastic differential form

where and

are more formally referred to as drift and volatility. Expression (5) appears in the well known Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model. It is, however, an incomplete characterization of our particular chaotic system. This is because our information space is no longer a closed system, rather one that is interacting with another chaotic system with a systematic influence on the state variable

. As a result of this, the variability of distribution throughout time is no longer constant. Our system is said to be heteroskedastic. In order to account for this non-linearity we can relax orthogonality by introducing a function

that describes the relationship between these interacting systems

Let us define a that is some linear combination of our closed system,

, and the outside system,

. We can formalize this interpretation by writing out the total differential form

which can be re-written as

Now lets assume that

which implies

where . For

the above expression reduces to

assuming zero constants of integration and where and

are independent

. Based on this we can define the following

where and

describes the interaction between stochastic systems

and

. Solving for

and

we have

Therefore, it follows

Given the result above, we can re-write (6)

In the next chapter we will outline the steps that solve for , extending these results to derive an n-state CAR framework.